CHINA INC. CONFERENCE – 22-23 FEBRUARY 2014 in Cairns, Queensland.

This paper seeks to imprint the names of Yung Sing (William Young Sing) and Yung Doong (Ah Goon) on the radar maps of Chinese-Australian research in the hope that future studies uncover archival references related to their repatriation of their earthly remains from Australia and possibly leads to their location in Guangzhou (Canton), China.

Australian Government records and historical press reports, sourced to date, validate the death, burial and also the exhumation of Yung Sing (William YoungSing) and Yung Doong (Ah Goon).

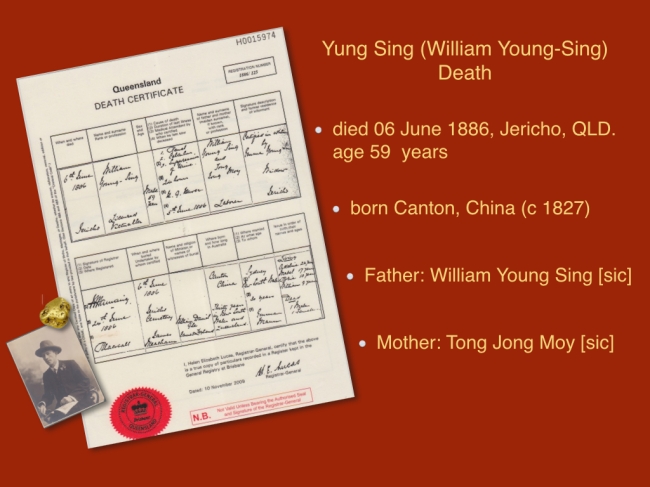

YUNG SING known as WILLIAM YOUNG SING

According to his Queensland death registration, Yung Sing (William Young Sing) died 06 June 1886 at Jericho, Queensland and was buried on the same day. A Chinese Merchant, this document stated he arrived in the Colony (Sydney) about 1856.

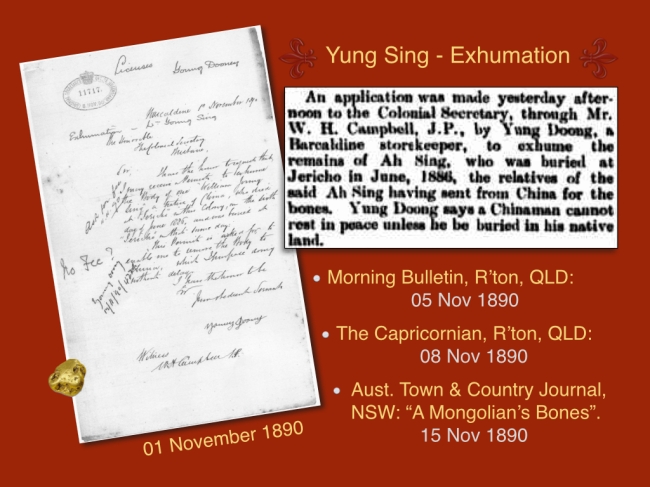

On November 1890, Yung Doong (Ah Goon), a Chinese storekeeper in Barcaldine, applied for a licence at the local Police Magistrate to exhume or disinter William Young Sing’s remains in Jericho. This legal process was in accordance with Australian Government requirements.

Because of this application, there is no doubt that Yung Doong was a close associate of William Young Sing and ‘more than likely’ to be a member of the same Chinese Clan Society. The licence was granted on 13 December 1890 by the Colonial Secretary in Brisbane, Queensland. Many Chinese belonged to a society and contributed monies to assist old Chinese men who could not afford to return to China or following a certain time after death, these clan societies took steps to exhume the remains of their members with the view of re-interring them in their native land.

It is believed the exhumation of William Young Sing was performed shortly thereafter in preparation for the long and final journey to repatriate his earthly remains with his Chinese family ancestors in accordance with Chinese spiritual and cultural practice. The village and burial location in Canton (Guangzhou), China is yet unknown.

It is understood his remains were possibly cleared through the Tung Wah Columbarium in Hong Kong according to Chinese Government health requirements. Archives in relation to repatriation of their remains have yet to be sourced. The Tung Wah Archives are, of course, in Chinese language and characters.

AH GOON known as YOUNG DOONG

On 11 June 1900, Yung Doong, Chinese Storekeeper died from Intestional Peritonitis at Barcaldine, Queensland aged 49 years. His Queensland Death Registration states he was born in Canton (Guangzhou), China.

Young Doong was well-known and had been a storekeeper on the Central Railway Line for over twenty years, and being of a charitable disposition, had been foremost in providing contributions to charitable causes (as did many of Chinese).

A cultural procession and Chinese funeral service celebrated at the local Barcaldine cemetery was worthy of note in the local newspaper, “The Western Champion and General Advertiser.”

Many prominent Chinese residents attended his funeral from Rockhampton and other districts, the Cortege was headed by the Barcaldine Brass Band (consisting of many Jimmy Ah Foo family members). Chinese Rites were observed at the graveside, which was of great interest to the general public (see article).

Young Doong died intestate and there was a scramble to administer his estate after his death. Many reports appeared in the Barcaldine and Rockhampton press. Young Sam, another Chinese claimed he was the “Brother” then placed an advertisement in Barcaldine a week later to claim he had made a mistake and was in fact the “Uncle.”

Eventually Young Chow, the authentic ‘Brother” was granted administration over Young Doong‘s estate and probably with Young Sam, began trading at the store in Barcaldine by the end of 1900 as Young Chow & Co.

On 05 April 1905, the Sydney Morning Herald reported “a number of Chinese at Barcaldine exhumed the body of Young Doong. It transpires that the Chinese Secret Society is exhuming bodies to re-inter them in China.”

The exhumation of Young Doong was of such interest to the general public in Barcaldine that a local correspondent took the time to investigate and research this particular Chinese cultural and spiritual practice from a local prominent Chinese businessman and publish them in the “Western Champion and General Advertiser” on 10 April 1905.

This article explains in detail the exhumation practice from the Chinese perspective and rich cultural funerary practices. It provides an ‘inside story.” A summary of this article for the purpose of this paper follows:

The Exhumation Licence was granted on 08 March 1905. This followed an application in writing by Mr. W. J. Savage of the Barcaldine Cemetery Trust at the request of another Chinese storekeeper, Wah Sung. Follow-up correspondence was received at the Colonial Secretary’s Office in Brisbane, both letters were indexed in January 1905, but the originals have eluded the filing system and have yet to be sourced at Queensland State Archives.

William Young Sing and Yung Doong both signed a petition in 1885, to support a Chinese Market Gardener named Sing Noy to retain his allocated market garden at Lagoon Creek, near Barcaldine. A prominent grazier, who had been granted this parcel of land wanted to remove Sing Noy and his garden even though the gardener was already established before the arrival of the Central Rail Line and had incurred costs of 50 Pounds.

Yung Doong also gave assistance to William Young Sing‘s wife Emma, when she applied for estate administration after he died intestate on 06 June 1886. This also confirms a trusted and close connection between them. The other creditor named was William Henry Smith, Emma’s new son-in-law, a saddler.

Emma Young Sing gave evidence in court at Barcaldine on 01 March 1887 to provide an alibi for Young Doong at a time when he was charged with selling rum from his store without being licensed to an undercover policeman. Emma stated that Young Doong was visiting her store in Jericho on the day, another confirmation of the close connection between the Young Sing‘s and Young Doong.

Published Commercial Reports between 1858 and 1866 confirm exported substantial gold consignments to Hong Kong and bulk quantities of preserved fish from The Rocks, New South Wales to a network of Chinese merchants and Chinese storekeepers on the goldfields in New South Wales and also Victoria.

According to his daughters’ New South Wales Birth Registrations, William Young Sing resided with his wife Emma (nee Mann) at 117 Gloucester Street, Sydney (The Rocks). He was part of a small Chinese merchant activity and stores which were set up to service the Chinese influx of sojourners who were seeking the gold in the 1850s and 1860s. This location of Lower George Street and Essex Street corners fostered the first commercial area of Chinese traders in New South Wales. European clerks or historians may call it “China Town” but this name did not exist for the Chinese.

William Young Sing, merchant was already involved in substantial business activities before his arrival to Sydney. The amount of gold quantities which he was exporting confirms that he was a trusted member of his Chinese Clan Society and was exporting gold back to China via Hong Kong on behalf of the Chinese associated with his Clan – he was an ‘agent’ – a kind of ‘banker’ and for this to occur – even at the Chinese end, with gold being delivered in person to their families, trust was an important factor.

On 10 February 1862, Yung Sing married Emma Mann, of Parramatta, daughter of John Mann and Ellen Lyons. Alternative names for John Mann on her sister’s marriage and death registrations list John Mann as other names such as Fung Mann, Foong Mann and Fong Mann. Ethnic origin of John Mann has yet to be proved.

The marriage was listed in the Sydney Morning Herald on 17 February, 1862 and also made waves in an editorial on New South Wales in the London Gazette, dated May 1862. It is clear that Yung Sing was a merchant of some standing.

He certainly had his “finger on the pulse” and was trusted with the “inside story” on where the Chinese were striking it lucky with substantial gold finds. Why else would he leave his Chinese contingency and relocate to the early settlement of Crocodile Creek Diggings in October 1866 near Rockhampton in Central Queensland? The only answer is the gold and the business wealth which accompanied a substantial gold diggings. It is apparent that he traded with both the Chinese and the Europeans. There is no doubt that substantial gold quantities passed through William and Emma Young Sing‘s hands.

William Young Sing was a Licensed Victualler at Crocodile Creek Diggings from 1866 to 1872, when he transferred his licence to Charles Ah You.

The Queensland Hotels and Publicans’ Indexes (1843-1900) reveal William Young Sing was also a Licensed Victualler at other early settlements such as Copperfield, Emerald, Bogantungan, Pine Hill until his death in June 1886 at Jericho, a Central Queensland Railway terminus community.

From press reports, we know William Young Sing also resided at Cooktown/Palmer River Goldfields in the late 1870s, but a Publican’s licence has yet to be located there. He had a close connection with Jimmy Ah Foo and family connections remained long after they both passed away – even into the great grand children of today.

CONCLUSION: